|

By Shelby Gibson “Hey! Are you looking for Pokemon?” one of the boys yelled across the road. After a moment or two of delay, I realized he was talking to me. Caught off guard, I wasn’t sure exactly how to respond. I wasn’t looking for Pokemon. With a butterfly net large enough to catch a small dog, I was neck deep in tall-grass and wildflowers along the side of a back-country road. I was searching for bumble bees. It had been reported that a somewhat rare species had previously been found at this location. That’s what I was looking for. In a way, I guess I was searching for a Pokemon. While I didn’t find the rare species that I had been after, I did manage to find a great diversity of bumble bee species at this location. What many people don’t know is that there are nearly 20, 000 different species of bees in the world. That’s right! 20, 000. When we think of bees it is often of the honeybee, doing our agricultural housekeeping for us. Humans and honeybees have a relationship that dates back thousands of years. For centuries, we have observed the honeybee as a social colony, as a pollinator of our food, and as a producer of honey. Similar to the relationship we might now have with a dog, honeybees historically played an important role in human civilization. With that kind of history, it is no wonder the honeybee is the most prominent pollinator we think of today. When we do so, however, we are forgetting the wild, native bees that surround us every day. With the knowledge that there are 20, 000 species of bees in the world, and that honeybees make up just 1, searching for these wild bees can become like searching for a Pokemon. Some bees are so common it seems as though they are everywhere. Some bees choose to make an appearance every couple of years or so. Some bees an avid biologist might only have the chance to see once in their lifetime. These are the bees that exist in the wild, living in their native habitat, ensuring the continued health of the ecosystems and agricultural systems around them. In turn, ensuring the continued existence of human populations. So, when we think of the bees, we should acknowledge the wild ones, who truly are the bee’s knees. Perhaps we should get out there and search for that Pokemon, the one that we might only see once in a lifetime.

0 Comments

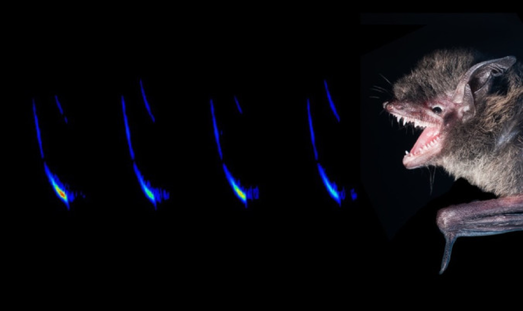

By Toby J. Thorne Bats are rather mysterious creatures. Most people I talk to about bats think they are interesting, but don’t know much about them. It’s not all that surprising, unlike more obvious wildlife such as birds, people don’t encounter bats very often. After all, they are active at night, when people like to sleep. Even then it’s hard to spot small and flying creatures in the dark. Happily, surveying bats is easier than it appears. Most bats (and all the ones found in Canada), find their way around in the dark using echolocation. Echolocation is the technique of emitting sounds and listening to the echoes to avoid obstacles and find prey. We don’t hear these sounds because they are at higher frequencies than we are able to hear. However, there are a variety of devices known as ‘bat detectors’ that can convert the sound into our hearing range. Some can make recordings that can be analysed later. With a bat detector in hand it is as if the bats are flying around shouting ‘I’m here! I’m here!’ What’s more, different species make different sounds, so it’s sometimes possible to identify the species of a bat based on its echolocation calls. Some species are more difficult to tell than others. The technologies, although improving, are far from perfect  A picture of a little brown bat along with a spectrogram of its echolocation call. Spectrograms are visual representations of the frequency, temporal and amplitude characteristics that are used by bat biologists to try and identify species based on echolocation calls. The bat’s mouth is open to facilitate echolocation, rather than in aggression. Photo by Toby J. Thorne Surveying bats through their sounds provides a huge opportunity to understand where they are and what they are doing. Listening to bat sounds forms a large part of my life. From summer evenings out listening to bats to winter days analysing recordings from the past year. For a number of projects I collect data throughout out most of the year with automated recorders. They stay out in the field for months at a time, recording any bats that fly by between dusk and dawn. I also lead regular bat walks and surveys through the summer, listening to and recording bats as we go. With new technologies around the corner, and a lot of attention being paid to acoustic monitoring in bats, I expect this aspect of our monitoring is going to grow. However, while acoustics presents a powerful, and non-invasive means to learn about what the bats are up to, it can’t answer all of the questions that are key to effective conservation programs for bats. Four of the eight species of bat in Ontario are now listed as endangered under the provincial species at risk act – all within the past five years. The decline of these species is driven primarily by White Nose Syndrome (WNS). WNS is a fungal disease that arrived in Ontario in 2010, and affects species that hibernate in caves. Our knowledge of the pre-WNS populations of these species is very limited, but counts at hibernation sites found average declines of 92% following the arrival of the fungus. The endangered bats in Ontario, along with those that aren’t currently listed as such, also face pressure from habitat loss and increasing urbanisation. Acoustic monitoring contributes a great deal to our understanding of Ontario’s bats, and therefore to their conservation. However, we cannot ‘hear’ the answers to many vital questions, such as whether the bats in an areas are healthy or reproductive. To answer questions like these we have to take the next step of catching bats. As with any invasive approach with wildlife, we have to think carefully about the decision to capture bats and the disturbance caused to individuals encountered. However, there is no substitute to having a bat in the hand in order to understand the population in the area. For a skilled bat biologist it is very quick to determine species (more definitively than is possible by acoustics for many species), sex, breeding condition and whether the bat is young of the year. Bats in Ontario continue to face a difficult time. Through the combination of methods such as acoustic and trapping surveys we are learning more about them than ever before. We can only remain hopeful that this new knowledge translates into some positive outcomes for our remarkable bats!

|

ELB MembersBlogs are written by ELB members who want to share their stories about Ontario's biodiversity. Archives

January 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed