|

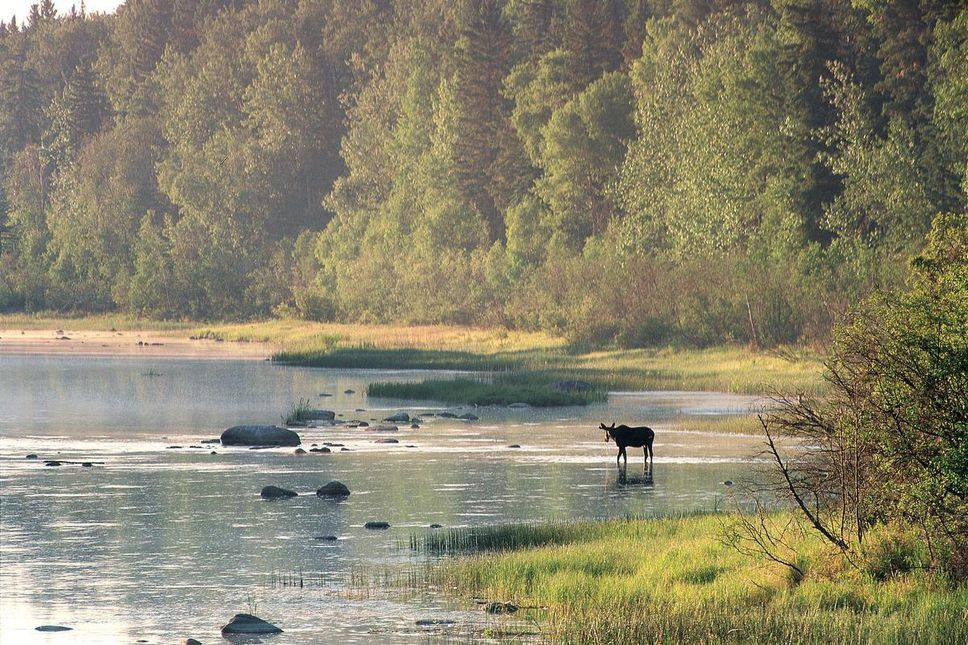

by Sara Mak This is part two of an article series by Sara Mak. Please view the last ELB blog post to read part one. By 2020, Canada aims to complete 19 biodiversity targets—it’s ambitious, but achievable! These targets vary widely in terms of their scope, difficulty, and level of detail. Just to give an example, here are Targets 6 and 1: Target 6: By 2020, continued progress is made on the sustainable management of Canada’s forests. Target 1: By 2020, at least 17 percent of all terrestrial areas and inland water, and 10 percent of coastal and marine areas, are conserved through networks of protected areas and other effective area-based conservation measures. In addition to preserving and enhancing biodiversity within the country, these targets also ensure long-term environmental stewardship and participation from all Canadians. Examples of this include the incorporation of biodiversity into the school curriculum as well as the adoption of more ecosystem-based approaches in agriculture and aquaculture. Another aspect to the success of the biodiversity targets is the involvement of Indigenous groups. While they may only make up 4.9% of the national population, they possess the traditional knowledge and skills Canada needs moving forward. As for current involvement, Zurba et al (2019) describe a few fundamental roles including consultation, management, or governance. Indigenous involvement in the management of Canadian ecosystems isn’t limited only to the completion of the biodiversity goals. Over the years more opportunities have been made available for Aboriginal groups. Through the First Nations Land Management Act, funding is available for establishing land and managing the environment and natural resources within it. This collaboration is ideal not only for Canada’s ecosystems but also as an opportunity to strengthen the relationship between the Government and First Nations groups. As a member of the UN’s CBD, Canada is required to regularly submit national reports summarizing their progress with regards to the adoption of the Convention. For the last few years, these reports have also detailed the progress made on each of the biodiversity targets. And with 2020 just around the corner, Canada seems to be on track to accomplishing most of its goals. The 6th National Report tells us that (good news!) most of the targets are moving along with steady progress. Some of the targets are seeing slower progress but there are renewed efforts to pull through during this final stretch. Steady progress: As of spring 2019, 11.8% of Canada’s land and freshwater is conserved, according to the Canadian Parks Council. Photo from the Toronto Star. Canada has acknowledged that Indigenous knowledge is invaluable and that the success of the biodiversity targets is dependent on meaningful collaboration between all levels of government and Indigenous groups. As such, their contributions are spread amongst all of the goals. In addition, of course, to the two dedicated to the improvement of Indigenous rights to the environment (Targets 12 and 15). Representatives from First Nations, Inuit or Métis peoples also participate as members of the Canadian delegation during meetings with the CBD and directly influence current and future plans as advisors. Conclusion What better way to combat extinction than by increasing biodiversity? Through the UN’s CBD, the international community is committing to a more sustainable and hopeful future by working towards improving global biodiversity levels. As the country with the second largest landmass and a reputation for natural beauty, Canada has its work cut out. Deadline aside, we need to look further than just the completion of the targets. Securing Canada’s environmental future will take long-term planning — some of which was established through the targets and commitment, as well as partnerships with Indigenous groups. After all, Canada has a lot to protect. It will take a lot of work to adapt to the changing environment, but our future depends on it. References McCall, R. (2019). Human actions are putting the survival of a million species on the line. IFL Science. Retrieved from: https://www.iflscience.com/plants-and-animals/human-actions-are-putting-the-survival-of-a-million-species-on-the-line/ Schuster, R., Germain, R. R., Bennett, J. R., Reo, N. J., & Arcese, P. (2019). Vertebrate biodiversity on indigenous-managed lands in Australia, Brazil, and Canada equals that in protected areas. Environmental Science & Policy, 101, 1-6. Wilson, K. (2019). Indigenous-managed lands have the greatest biodiversity, says UBC-led study. The Georgia Straight. Retrieved from: https://www.straight.com/news/1281011/indigenous-managed-lands-have-greatest-biodiversity-says-ubc-led-study Zurba, M., Beazley, K. F., English, E., Buchmann-Duck, J. (2019). Indigenous protected and conserved areas (IPCAs), Aichi Target 11 and Canada’s pathway to Target 1: focusing conservation on reconciliation. Land, 8(1), 10.  About the Author Sara’s love of animals and the environment is what led her to study Geography and Environmental Management at the University of Waterloo, and as a recent graduate, she hopes to further pursue her passion in wildlife conservation. In her free time, she loves stargazing, hiking and exploring the great outdoors (preferably with her dogs)!

8 Comments

by Sara Mak We are in the midst of a mass extinction event. And unlike the five previous mass extinctions (which were caused by large-scale natural phenomena such as widespread volcanic activity or a huge chunk of space rock colliding with the earth’s surface), this one is on us. Throughout history, humans have fought to control nature and use its resources for human advancement. Indeed, no other species in Earth’s 4.3-billion-year history has ever had such a significant impact on the planet in such a short amount of time. As the name suggests, a mass extinction event occurs when many flora and fauna species are at risk of being wiped out. In fact, the United Nation’s 2019 Global Assessment Report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services reports that one in four (or approximately one million) species is facing extinction — 1,000 to 10,000 times more than natural background rates (Wilson, 2019). Vancouver Island marmots are the most endangered mammal in Canada. They, alongside countless other species, are on the verge of extinction. Photo by Jared Hobb. Time is running out. Now that we are able to see the damage (both because of modern advances and because of the exacerbated effects of climate change), we need to take immediate action. Mass extinction is not something that can be reversed with a simple “ctrl + z”, however, since we were the catalysts, perhaps we can be the solution as well. What’s the plan? First and foremost, the contribution of the international community is key. In 2010, the United Nations Convention for Biological Diversity (CBD) created the Strategic Plan for Biodiversity, which comprises of five strategic goals:

Second, and perhaps just as important as the leadership of the international community, is the participation of Indigenous communities. A study by Schuster et al (2019) found that lands managed or co-managed by Indigenous communities had the highest levels of biodiversity. Compared to other methods, Indigenous land practices tend to be less exploitative, which means less deforestation and land degradation, as well as more sustainable forest use. Currently, one-quarter of Earth’s land surface is designated Indigenous land. With their help, we can apply the environmental stewardship demonstrated in these areas on a global scale. Thaidene Nëné, a protected-area zone co-governed by the Łutsël K’é Dene First Nation in the Northwest Territories. Photo by Pat Kane.

|

ELB MembersBlogs are written by ELB members who want to share their stories about Ontario's biodiversity. Archives

January 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed