|

By Shelby Gibson While the weather may not be a good indication, now is the perfect time to start the process of growing many of Ontario’s native plants. Growing native plants is becoming an increasingly important skill as more restoration projects focus on growing native species, and as home gardeners try to support declining pollinator populations. There is an increasing interest in growing native plants, however growing them is different from many other commonly grown garden plants. When growing native plants from seeds germination rates will be partially determined by the method of seed preparation used. Many native plant seeds need to be started in the fall or winter. There are various methods of preparation which are used to break the seeds dormancy and encourage germination. A process called cold stratification is used to mimic outdoor conditions that the plant would experience in its natural environment. This means placing the plants in the fridge for a period of time prior to germination (e.g. 60 days) inside a plastic bag or container. The length of time the plants undergo cold stratification varies between species. Another factor is moisture, meaning some plants need to undergo cold moist stratification. In this case, a source of moisture, such as a damp paper towel, is placed in the container or bag with the seeds during stratification. Yet another type of preparation required by some seeds is scarification, where the outer layer of the seed needs to be physically broken down in order for germination to occur. This can be done with items such as sandpaper. After their preparation period, native plant seeds can be started in a soil mixture in pots or trays. Some require being placed inside the soil while others require simply being sprinkled on top of the soil. The diversity of ways to start native plant seeds represents the great diversity of native plant species the seeds produce. Diversity in methods of preparation and growing means that native plants can be somewhat more complicated to get going. It is important to learn the requirements of each plant prior to beginning in order to ensure that each particular species is prepared correctly. This will lead to increased success with germination and eventually with transplanting the seedlings outdoors. Healthy seedlings are important to the success of planting and restoration projects, and therefore the skill of growing native plant seedlings is important as well. Growing native plants from seeds can be a highly satisfying experience, with the added bonus of providing food for some of Ontario’s native fauna! Helpful Resources: Native Plant Network – Propagation Protocols; https://npn.rngr.net/propagation/protocols Indigiscapes.com – A Native Plant Propagation Guide and Nursery Model; https://indigescapes.com/blog/printed-version. North American Native Plant Society – Indoor Native Seed Stratification; https://nanps.org/96358-2/. And always be sure to follow the ethics of seed collection: North American Native Plant Society - Seed Collecting; https://nanps.org/seed-collecting/. Blooming Boulevards - Seed Collectors Code of Ethics; http://www.bloomingboulevards.org/ethical-standards-forr-naseed-collecting.  About the Author Shelby Gibson (B.Sc., M.E.S.) is a PhD Candidate at York University using a biocultural lens to further understand plant-pollinator interactions. Shelby's research focuses on native medicine plants and other culturally significant plant species. Shelby is interested in solving conservation-related problems using a social-ecological perspective. Follow along on Twitter to keep up with research updates! (@GibsShelby).

3 Comments

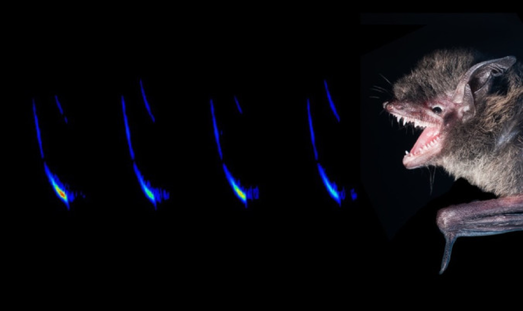

By Toby J. Thorne Bats are rather mysterious creatures. Most people I talk to about bats think they are interesting, but don’t know much about them. It’s not all that surprising, unlike more obvious wildlife such as birds, people don’t encounter bats very often. After all, they are active at night, when people like to sleep. Even then it’s hard to spot small and flying creatures in the dark. Happily, surveying bats is easier than it appears. Most bats (and all the ones found in Canada), find their way around in the dark using echolocation. Echolocation is the technique of emitting sounds and listening to the echoes to avoid obstacles and find prey. We don’t hear these sounds because they are at higher frequencies than we are able to hear. However, there are a variety of devices known as ‘bat detectors’ that can convert the sound into our hearing range. Some can make recordings that can be analysed later. With a bat detector in hand it is as if the bats are flying around shouting ‘I’m here! I’m here!’ What’s more, different species make different sounds, so it’s sometimes possible to identify the species of a bat based on its echolocation calls. Some species are more difficult to tell than others. The technologies, although improving, are far from perfect  A picture of a little brown bat along with a spectrogram of its echolocation call. Spectrograms are visual representations of the frequency, temporal and amplitude characteristics that are used by bat biologists to try and identify species based on echolocation calls. The bat’s mouth is open to facilitate echolocation, rather than in aggression. Photo by Toby J. Thorne Surveying bats through their sounds provides a huge opportunity to understand where they are and what they are doing. Listening to bat sounds forms a large part of my life. From summer evenings out listening to bats to winter days analysing recordings from the past year. For a number of projects I collect data throughout out most of the year with automated recorders. They stay out in the field for months at a time, recording any bats that fly by between dusk and dawn. I also lead regular bat walks and surveys through the summer, listening to and recording bats as we go. With new technologies around the corner, and a lot of attention being paid to acoustic monitoring in bats, I expect this aspect of our monitoring is going to grow. However, while acoustics presents a powerful, and non-invasive means to learn about what the bats are up to, it can’t answer all of the questions that are key to effective conservation programs for bats. Four of the eight species of bat in Ontario are now listed as endangered under the provincial species at risk act – all within the past five years. The decline of these species is driven primarily by White Nose Syndrome (WNS). WNS is a fungal disease that arrived in Ontario in 2010, and affects species that hibernate in caves. Our knowledge of the pre-WNS populations of these species is very limited, but counts at hibernation sites found average declines of 92% following the arrival of the fungus. The endangered bats in Ontario, along with those that aren’t currently listed as such, also face pressure from habitat loss and increasing urbanisation. Acoustic monitoring contributes a great deal to our understanding of Ontario’s bats, and therefore to their conservation. However, we cannot ‘hear’ the answers to many vital questions, such as whether the bats in an areas are healthy or reproductive. To answer questions like these we have to take the next step of catching bats. As with any invasive approach with wildlife, we have to think carefully about the decision to capture bats and the disturbance caused to individuals encountered. However, there is no substitute to having a bat in the hand in order to understand the population in the area. For a skilled bat biologist it is very quick to determine species (more definitively than is possible by acoustics for many species), sex, breeding condition and whether the bat is young of the year. Bats in Ontario continue to face a difficult time. Through the combination of methods such as acoustic and trapping surveys we are learning more about them than ever before. We can only remain hopeful that this new knowledge translates into some positive outcomes for our remarkable bats!

|

ELB MembersBlogs are written by ELB members who want to share their stories about Ontario's biodiversity. Archives

January 2023

Categories

All

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed